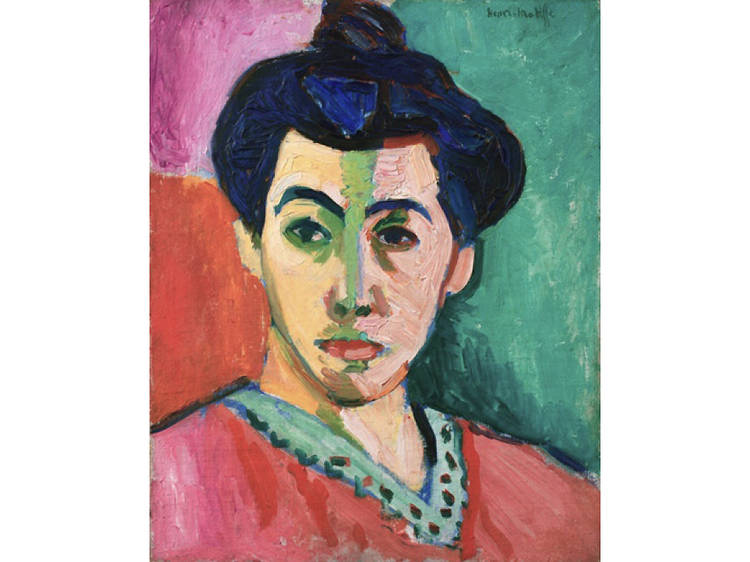

1. Portrait of Madame Matisse (The green line), 1905

As a young man, Matisse studied with the Symbolist painter Odilon Redon, but he paid close attention to work of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. Initially, he adopted the pointillist techniques of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, and even became an acquaintance of the latter. But in time, Matisse moved on from dashes and dots to broader planes of color that abandoned any pretense of realism. Matisse used color for its own sake, becoming a leader of the Fauves along with Andre Derain. Perhaps the first true avant-garde movement of the 20th-century, Fauvism outraged critics of the day with seemingly haphazard applications of pure color. This likeness of Matisse’s wife is a case in point. It transforms her face into a mask divided in the middle by a green stripe, abstracting her features and the wall behind her into a chromatic jigsaw puzzle.

Portrait of Madame Matisse is currently on display at Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen.

Check out more of Copenhagen's best museums.